The business of the third space

Surrogate third spaces, the rise of the fourth space, and the disappearance of a home away from home

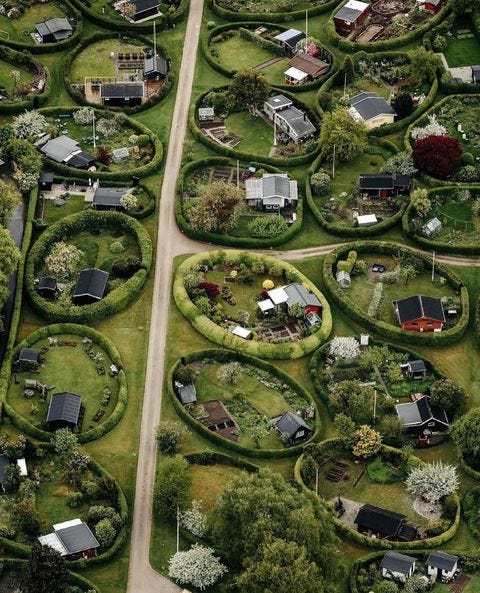

The neighborhood I live in is a company. Eur S.p.A. is a publicly owned corporation controlled by the Ministry of Economy and Finance and the City of Rome, with assets that include the district’s main historical buildings, cultural hubs, and all the green areas within the so-called “pentagon” of the 1942 Universal Exposition, from the Eucalyptus Park to the Central Lake. In short, my neighborhood is by definition a semi-public space – that is, a place which, although ostensibly open to community use, is managed and maintained by a company that, at any moment, can choose to operate according to market logic. This could mean selling or leasing certain areas for commercial purposes, or regulating access based on interests that don’t necessarily align with those of the public who use the space every day.

In theory, my neighborhood structurally embodies everything a third space is not supposed to be.

First theorized in 1989 by sociologist Ray Oldenburg in his essay The Great Good Place, the third space is presented as the defining element of all those places where individuals can spontaneously socialize outside of their domestic environment (the first space) and their professional setting (the second space).

According to Oldenburg, the concept of the third space includes public places such as parks, community centers, public libraries, and markets, as well as small businesses like cafés, pubs, bookstores, and theaters.

What distinguishes a third space, however, is not simply its accessibility to the public, but the type of atmosphere and participation it is able to foster: third spaces are all those that encourage both personal and collective enrichment, that ensure inclusive engagement without economic barriers or affiliation requirements, and that serve as neutral grounds welcoming people from vastly different backgrounds.

These are environments where conversation and verbal exchange fuel social interaction, and where one can feel comfortable even when surrounded by strangers. Oldenburg captures the essence of the third space with the metaphor of a “home away from home,” drawing on the insights of psychologist David Seamon to outline the key features needed to convey a sense of domestic familiarity (or homeness) to the community: the ability to instill a sense of rootedness and belonging, the creation of a comfortable place where one can feel at ease, and finally, the capacity to offer a refuge for spiritual restoration. The third space is the place of kinship, a relational network that is shifting, fluid, and constantly expanding.

And yet, the third space today is also a marketing trend. According to the latest report from trend forecasting agency WGSN, aligning brands and services with the logic of the third space can help engage a target audience seeking an antidote to urban and digital alienation. Within the study, wellness and fitness events held in city green spaces, or small in-store workshops, are presented as possible experiences to be sold as (branded) constructions of third spaces, even as they betray the core principles that Oldenburg saw as fundamental to their very existence.

The commodification of the third space is particularly evident in the tourism sector: home away from home has become synonymous with a vacation setting that blends elements of exoticism with a daily routine designed to immerse guests in a timeless flow, punctuated with carefully curated moments of novelty and wonder. In these contexts, community becomes a mere accessory to personal experience – the exotic element, the reassurance that we are living our lives accompanied by the ambient noise of others. Just enough to avoid calling it solitude.

Re-enchantment – the renewed sense of wonder in the everyday, which dominated marketing trends just last year – returns in a less flashy, more subdued version: this year, the antidote to the numbness and deep isolation of the 21st-century Western individual is the “business of the third space.” In a socio-economic landscape where luxury and exclusivity have become relative, all that remains is the attempt to repackage as new commodities the lost elements of a modern experience that now belongs to the past. Communities –and the spaces in which to cultivate them – are certainly among those lost elements.

The web has played a fundamental role in the dilution of third spaces.

Just like semi-public spaces, tourist experiences, and services that sell the possibility of “building new meaningful connections,” today’s web is a surrogate third space – a place where private commercial interests disguise themselves to take advantage of the sociality generated within.

And yet, many of us, including myself, grew up in these so-called third spaces. That’s where it becomes difficult to distinguish between nostalgia for an inclusive, diverse, and familiar community like those described by Oldenburg, and nostalgia for a fictitious community, already tainted by the shadows of commerce and surveillance, even if the old web did represent –for a brief time – an authentic third space.

It’s precisely this nostalgia that fuels the spread of the third space business online as well, where a new wave of startups offers digital spaces and apps to help you find your own third space with just a click. These include apps for making new friends or joining group events and activities, as well as an app for tourists who want to have local experiences and locals who want to have tourist experiences, one for organizing your contacts and relationships by context, and one that promises to reinvent the idea of the neighborhood.

Is the third space dead? Long live the third space?

Maybe. The reality is that this might be a dimension we’ve lost forever. As economic geography professor Arnault Morrison observes in a study, in societies dominated by the information economy, the hybridization of places has transformed the third space into a new dimension: the fourth space.

The fourth space includes all those environments capable of offering the characteristics and functions of the first, second, and third spaces, and the interactions among them. As Morrison explains, these are residential, professional, and social projects materialized in coliving, coworking, and comingling spaces. The example he gives is the Stream Building in Paris, a relational and productive hub that offers micro-apartments, shared work areas, networking spaces, and dining options within a single circular building, where activities are carefully categorized: Stream Stay, Stream Work, Stream Play, and Stream Eat.

The formula of the fourth space is therefore one of hybridization and, at the same time, hyperspecialization: while the third space offered an “other” place to retreat to and cultivate extended relationships with no goal beyond collective enjoyment, the fourth space is a dimension in which every personal and professional boundary is dissolved, but not freed. All spaces are concentrated into a single container, where sociality becomes the illusory glue that enables control over the experience.

From this perspective, the fourth space is everywhere: in homes we use as offices, in networking on social platforms, in the experiences and social spaces of contemporary cities that give us the comfort of standardized personalization.

The fourth space reflects the very culture of the 21st century: the blending of relational and productive dimensions, the sharing economy, the endless substitution of the third space, the corporate neighborhood, and gentrification as an aesthetic. On the map, the way home is lined with work hubs, innovation centers, coffices, and business parks.

If the third space still exists, we won’t find it on GPS or in an app.

Maybe, at first, we’ll have to figure out on our own how to find our way back, hoping that, somehow, it leads us to a place where, at least briefly, even sporadically, we can finally rest. Without nostalgia, hierarchy, or performance. Without that unbearable feeling – comforting and terrifying at once – of always being alone in the crowd.